I have PTSD, and I hate myself for it. Unlike my Army buddies, I was not deployed, or even entered active service. Unlike many female friends, I was never sexually assaulted. I didn’t lose a limb, or bury a child, or come out, or grow up poor, or experience domestic abuse, or fight addiction. No, my trauma (I fought the urge to place the word in quotations) comes from two years on the Hudson River. And I feel weak, that I didn’t earn it, that I am unworthy of sharing a diagnosis with so many infinitely stronger people than me. But here I am nonetheless.

I carry an invisible weight at all times. It is a granite slab across my shoulders. Occasionally the yoke is almost imperceptible, to the point where I hope it’s dissipated forever. At other times, I’m crushed within an inch of my life. It doesn’t matter if I’m working, joking with friends, exercising, or reading—the burden is ever-present.

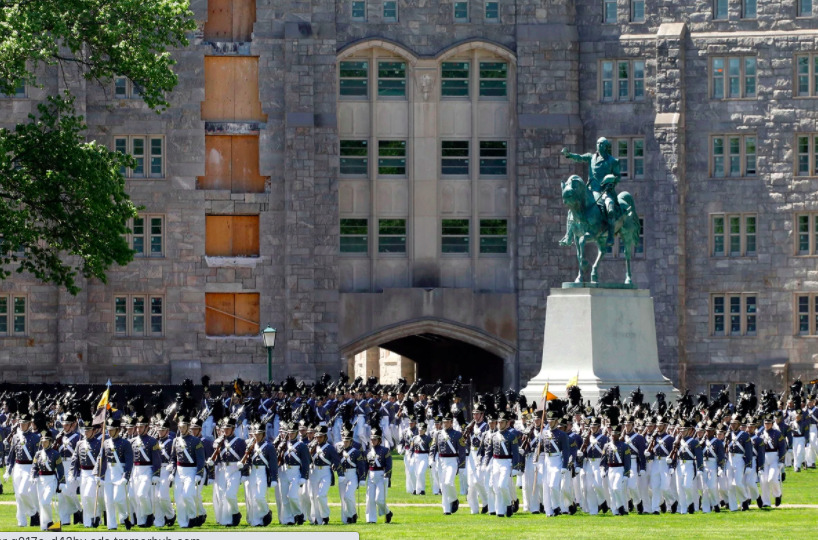

I experience a recurring nightmare. It’s actually quite boring. I sit across a desk from an Army Officer who explains that I did not correctly complete my paperwork when resigning my commission. I now have to redo all four years at West Point. I desperately assert that I’m in my 30s and not even eligible to attend the Academy. But the Officer persists, and I submit to my fate. I relinquish the struggle and disappear beneath the stone.

Why did the United States Military Academy leave such an enduring impression? Sure, I was exposed to an exceptionally rigorous academic schedule. I routinely slept four to five hours a night. I was dehumanized and hazed throughout my first year. Rucking for days with a heavy pack and broken shin was no fun. But the exhaustion, the physical and psychological rigor, were not why I chose to leave. The reason for that lies in my ethnicity.

I am Cuban-American. If you should learn one thing about Cubans, it is that we are loud. And proud. And loudly proud of how proud we are to be loud about being Cuban. Also, I was raised in Miami, the most proudly loudly Cuban locale on Earth. My second distinguishing characteristic is that I “don’t look Cuban.” My hair and skin are light, making me appear nothing like Desi Arnaz, Pitbull, or Ricky Martin (the latter is Puerto Rican but that did not stop many from making the breathless comparison). Assuming that anyone “looks Cuban” ignores the island’s integration of immigrants from Lebanon, Ireland, Germany, Spain, England, the Philippines, Haiti, Turkey, Korea, China, and the forced exodus of millions of enslaved Africans. But this demands historical and ethnographical nuance, which is often asking for too much.

It would be easy to claim that West Point was simply an intolerant environment that forced me out because I failed to conform. But doing so would paint an incomplete portrait. I did not help my situation. At least initially, I gleefully hampered it. You see, the Army loves uniformity. Hence the uniforms. But I sauntered into the Academy with my big, loud Cuban mouth, and couldn’t give a damn what people thought about it. This did not make me very popular. Indeed, I annoyed and alienated many Cadets who would’ve made excellent friends—an outcome I deeply regret to this day.

I experienced instant pushback. Superiors and peers alike insisted I remove my cross, stop speaking Spanish with my fellow Latino Cadets, and claimed they were unsure if I would remain loyal to the U.S. should war break out with Cuba. Being trained in the exquisite Cuban art of not taking shit from anyone, I wore the cross outside my uniform, spoke only Spanish for an entire day, and asked which side my compatriots would choose at the commencement of the upcoming and inevitable confrontation with Great Britain.

The anecdotes are endless. My Puerto Rican friend had a roommate whose uncle was a wizard in the KKK. In typical Boricua fashion, he punched his cohabiter in the face after the latter called him a spic. A truckful of White Cadets interrupted a pickup soccer game by yelling racial epitaphs at their Latino peers, cackling hysterically as they drove off. I was repeatedly, pointedly asked why I stole the spot of a more deserving non-Hispanic White.

Things turned ugly early my first year when I stated at a meal that immigration reform was moral and necessary. The nine other Cadets at the table simultaneously and reflexively deluged me in recriminations. Not to be outdone, individuals from other tables bolted over, surrounded my chair, and joined the cacophony. I wanted to swamp the country in criminals! I wasn’t a patriot! I wasn’t a real American! I yelled back for a time. Eventually, drowned beneath a tide of vitriol, I shut my mouth and took it. A portent of things to come.

But I still wouldn’t shut up. When I was called a janitor, spic, Fidel, drug dealer, communist, rafter, affirmative action Cadet, Scarface, boat rower, lettuce picker, the lawn service, and shark food, I simply hurled back what I thought were more inventive insults. Nevertheless, my fellow Cadets learned that the best way to get under the skin of this loud-mouthed Cuban was not to offend his ethnicity, but to deny it altogether. Quite exquisite torture.

Being Cuban-American defines much of my identity. By negating that fact, my fellow Cadets sought (perhaps unconsciously) to erase my essence. I could parry away isolated attacks, but when everyone joined the assault, I had no refuge, nowhere to decompress and heal. I was under siege, but the enemy was inside the castle, in every hallway, in every room.

I walked into West Point with a plátano, bistec empanizado, and tostón-fueled grease fire roaring in my belly. When others tried to extinguish it with weak, watery slights, it only grew in intensity. But they found a granite boulder, held it over the flame, and pressed with the collective weight of the entire, centuries-old U.S. Military Academy. The embers burned, the pressure built, but the conflagration was out.

I found temporary refuge with those who were also “othered:” Latino (6% of the population), Black (7%), female (14%), and foreign exchange Cadets (2%). I felt more in common with a guy from Jordan than a Wisconsinite. Friends of Puerto Rican, Colombian, Bolivian, Mexican, Honduran, Dominican, Jamaican, African American, and Cuban (there were three of us!) descent kept me sane. And a wonderful, hilarious mentor from Ponce was a godsend. He welcomed me and other lost Latinos into his home like family. But I always left their company. I always disappeared back under the stone.

I was oblivious to the source of my despair the day I left the Academy. It took many, many years to root out the overwhelming bewilderment, resentment, anger, and frustration I brought home. I just knew I was miserable, and so departed.

Try as I might to disentangle it, my experience at West Point persists as a knotted contradiction. It is my greatest source of strength and weakness. I am proud of my time on the Hudson River. I was pushed harder and further than I ever thought possible. I draw upon that when encountering new challenges. More importantly, West Point introduced me to systemic oppression, granting me real empathy for those unable to escape it after just two years.

But I resent the crushing sense of defeat I felt walking out Thayer Gate. I regret how I pushed away friends, family, and lovers because I was an emotional lockbox for years. I partly wish I had gone to the University of Florida after high school and been a drunken fool with my friends. Yet, a stubborn resistance remains that would never surrender the trials, hardships, and triumphs I experienced. Those two years were my crucible. I emerged far stronger than when I entered. I’ve yet to be crushed by the stone, though the weight caused a few cracks.

In retrospect, I can only fault my white classmates so much. Many were cornfed kids from tiny rural towns. I was often the first Latino they ever met, and certainly the first Cuban. Some, like my ex-girlfriend and roommates from Alaska and Illinois, remain friends to this day. I care about them and they for me. In 2005, “micro-aggressions” and “implicit bias” had another decade before entering common parlance. West Point was an unabashedly white space (as it’s been for centuries) with few minority enrollees and even fewer incentives to pressure the default ethnicity into empathizing with othered classmates. Without a doubt, some Cadets were very explicitly racist. The majority were simply ignorant. I was annoyed when repeatedly asked which guacamole I preferred, but most meant no harm by it, until some did.

I wrote the first draft of this piece five and a half years ago, on the 10th anniversary of my first day of Beast (Cadet Basic Training). I can’t count how many times it’s been redrafted, but I’m still unsatisfied with the outcome. Given the nature of the subject, I doubt I will ever be. Initially, I reflexively peppered the article with humor. I am, after all, a satirical writer at heart. I probably did this to make it an easier experience for the reader and myself. If I could find wit and absurdity in the most difficult years of my life, then they couldn’t possibly be that bad. Neither you nor I should dwell much on it.

The more I revised the essay, the more humor I cut. I know now I will carry this weight the rest of my life. I wish I could find levity in that, but at this point, I simply can’t.

Most who hear this story want to know, if I were forced back in time, would I re-enroll in West Point? The older I become, the harder it is to answer that question. I’m just tired of the nightmares.

If you like my stories, read the first free chapter of my book.