Image taken from Mario Ariza’s Disposable City. He’s a friend. Go read it.

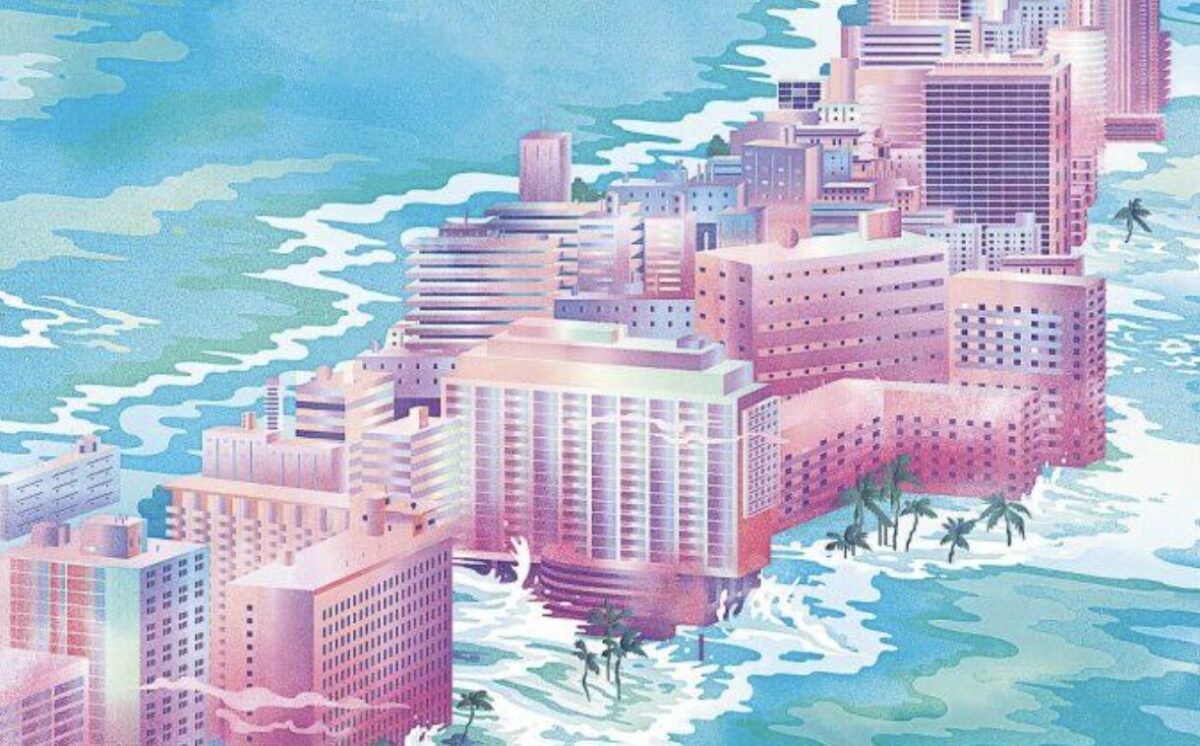

Miami faces an immediate existential climate change threat from stronger hurricanes and their associated storm surges. A direct hit from a Category 5 hurricane could cause catastrophic damage to South Florida literally any year now. We’re thankfully past hurricane season, but come June 2024, I know I’ll be right back to obsessively refreshing the National Hurricane Center’s tracker every two hours to see if its cones of uncertainty shift away from my hometown. We’ve been lucky over the last few decades, but anyone who lived through Hurricane Andrew knows it’s only a matter of time before we get dunked on again.

For those who didn’t experience that natural tactical nuclear strike, a hurricane’s greatest threat is not necessarily wind, but water. Now that the city practically stands still every time it rains for an hour or a king tide rolls through, we’re guaranteed massive flooding should a large storm deign it’s high time to visit the Magic City. We need only look to Hurricane Irma in 2017 when the whole of Brickell, Miami’s commercial and financial heart, remained underwater for days. And that wasn’t even a direct hit.

Hurricanes literally lift millions of gallons of water between three and 25 feet above the surrounding ocean. When they move inland, these walls of water go with them, inundating everything in their paths. This phenomenon is known as storm surge and it’s often hurricanes’ most destructive aspect.

To protect against this threat, Miami must transform itself into a green citadel by building an onion-like series of natural fortifications. The outermost layer of this defense-in-depth strategy lies a few miles into the Atlantic: a fully revitalized Florida Barrier Reef.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey, healthy offshore reefs act as natural speed bumps, reducing storm wave energy by as much as 97%. Florida’s reefs save residents an estimated $675 million in property damage every year. Unfortunately, approximately 90% of the state’s reefs died over the last 40 years due primarily to warmer ocean temperatures. Nevertheless, the University of Miami, Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium, and others are creating heat-resistant corals that can thrive in a hotter ocean. These breeding and replanting efforts must be scaled to industrial levels by private sector actors to have any hope of revitalizing Miami’s environmental economic engine and first line of climate defense.

Moving inshore, the next living bastion is a continuous line of artificial coral reefs just off Miami Beach. This project, known as the ReefLine, is already in motion.

Once a storm surge makes it past our outer defenses, it’ll hit a wall of ten-foot-tall sand dunes on Key Biscayne, Virginia Key, Miami Beach, and our other barrier islands. These will be reinforced with grasses, sea oats, and other native deep-rooted vegetation.

Having removed more than 23,300 pounds of trash from Miami’s mangrove forests, I’ve seen firsthand how their root systems soak up excess water like sponges while their resilient trunks dissipate waves’ kinetic energy that would otherwise destroy homes, streets, and businesses. We should plant new groves of these incredible natural shock absorbers everywhere we can along the water including rivers, canals, public parks, and private property.

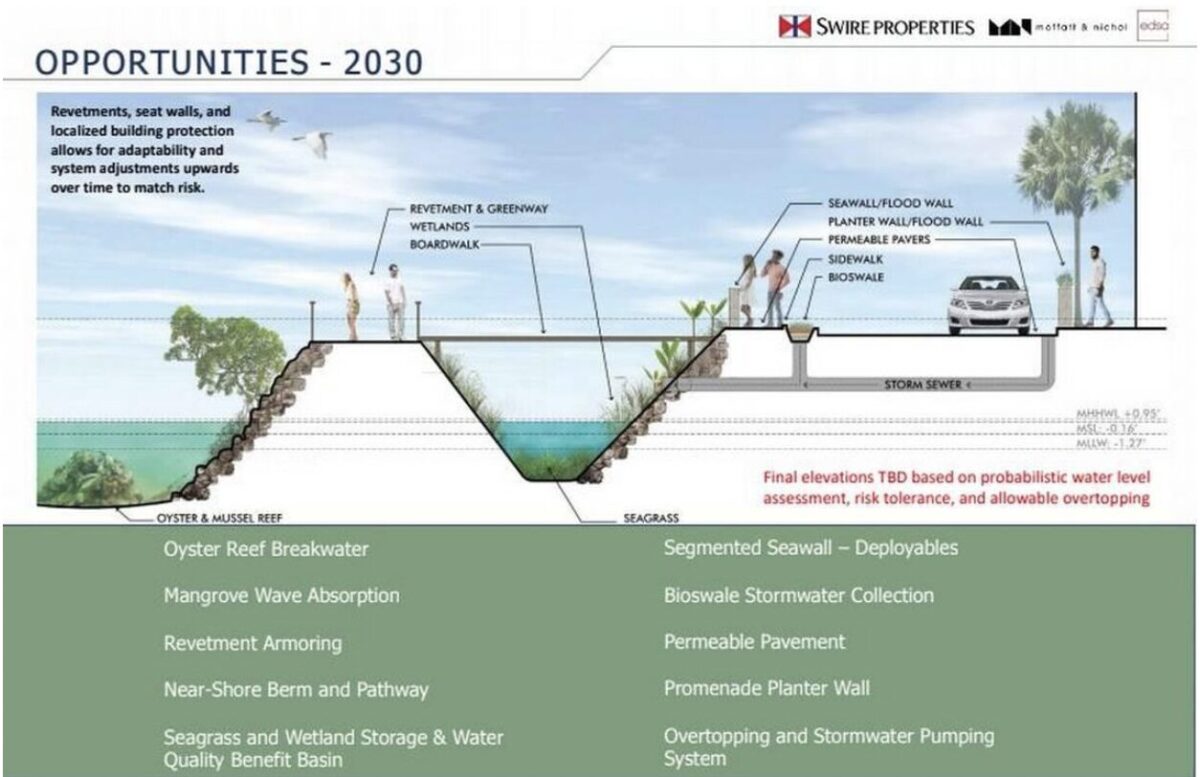

Next up is a fully fortified Biscayne Bay, whose spoil islands, breakwaters, and oyster reefs further reduce storm surges’ potency. Should water make it past this phalanx of defenses, it’ll run smack into a natural Theodosian Wall in the form of a living seawall. Composed of even more layers of oyster reefs, mangroves, corals, sea grass, elevated roads, and concrete seawalls, this will serve as Miami’s strongest line of defense.

Despite our best efforts, water might still breach this final barrier or accumulate inland as rain. That’s OK because we’ll be ready. Belts of new green spaces in parks and rewilded wetlands will act as reservoirs where water will be redirected and stored until it can dissipate, evaporate, or flow back into the ocean. Pumps and elevated roadways will help direct that excess water away from sensitive infrastructure.

The wonderful thing about these adaptation efforts is that all the new mangroves, oyster beds, and corals can spark a South Florida ecological Renaissance. They’ll clean our waters and create habitats that will spawn millions more coastal birds, rock lobsters, stone crabs, and reef fish, revitalizing our all-important eco-tourism sector.

But the dividends don’t stop there. As already exemplified by the Dutch, sustainability startups, ocean tech businesses, and green infrastructure companies will gain invaluable experience and expertise from converting Miami into a living citadel. They will create local jobs and gain international recognition they’ll then leverage to help other countries currently facing climate crises, thereby truly earning Miami’s recent designation as a climate tech hub and potentially serving as the tip of the spear of the recently announced American Climate Corps.

Funding

This will all necessitate a lot of money for a whole lot of stuff, but begging poverty as an excuse to not build infrastructure that actually helps Miamians rings utterly hollow. The city is currently constructing an absolutely useless $840 million spider bridge. Its residents were scammed out of $2.6 billion to construct a megalithic bleached turtle shell we call Marlins Stadium. Yes, we will need municipal, county, state, and federal dollars to complete these projects but we must also be much more creative about funding.

Rich people love putting their names on things: libraries, parks, museums, even bathrooms. It’s weird but they’re into it. Once we calculate how much each foot of living seawall, breakwater, or artificial reef costs to construct, I’d happily plaster them all with donor plaques. You can’t throw a frozen iguana around the MacArthur Causeway islands without hitting a resident billionaire. For a cool $1 million, Jeff Bezos can lay claim to a 20-foot section of wall, oyster bed, or an entire island. Ditto Ken Griffin. If Russian and South American oligarchs also want to launder their ill-gotten gains via tax-deductible seawall donations rather than time-honored real estate speculation, that’s cool too.

Condo management companies and homeowners’ associations whose properties border the shoreline should also join the effort. They’ll become especially receptive when they understand how the new defenses will lower their property insurance. Indeed, these climate adaptation measures can help reconstruct Florida’ collapsing homeowners insurance market once builders and buyers can argue that, no, our entire city will not definitely go underwater.

Finally, everyday Miamians must be engaged to assist this effort, not just through donations (for historical context, the Statue of Liberty’s pedestal was funded by more than 125,000 individual contributors) but through actual labor. I’ve led enough mangrove cleanups to realize Miamians have a deep-seated need to feel they are physically improving their environment. I’ve rarely seen people happier than when they’re covered in mud after bagging hundreds of pounds of trash because the work acts as a salve against climate despair. They did something good and they can see its immediate effects.

Have volunteers dig holes, plant mangroves, move rocks, fill sandbags, mix concrete, anything that will help solidify the thought that all is not lost and that anyone can help save their hometown.

You can’t spin a frozen Argentine tegu over your head in this city without smacking a half dozen influencers. Rope them into the efforts. Make building the living seaway a cool thing to do after Sunday brunch. Get visiting and local celebrities, heads of state, and politicians to join in. Want an endorsement for your political campaign? Forget Versailles and come excavate a trench at José Martí Park.

Who’s Driving This Crazy Train?

At this point, you’re probably wondering three things:

- Who or what is going to lead the effort to save Miami?

- When will this essay end?

- You’re such a talented writer, Andrew. Where can I buy your book?

I’ll answer in order of importance.

- Thank you. The book is called The Miami Creation Myth and you can buy it here.

- Soon enough.

- It’s complicated.

Let’s expand that last answer. I foresee a prominent local county policymaker convening a core group of corporate, civic, NGO, and community organizations to set a joint vision, mission, and objectives for saving Miami from climate change. They will incorporate a non-partisan, non-profit entity charged with managing the finances and logistics of doing just that.

Board seats will be apportioned to relevant government entities like the Division of Environmental Resource Management (DERM), the Army Corps of Engineers, and municipal environmental departments; economic development organizations like the Beacon Council and Chambers of Commerce; and civil society and activist organizations. The board chair would rotate regularly between different members to oversee an executive director and staff that execute their directives.

I know this might seem like an odd assortment of bedfellows, but all sectors need to pull in the same direction for a chance at saving Miami.

This being South Florida, whenever spending large sums of their money is involved, Miamians get justifiably nervous. All finances, contracts, and bid proposals should be made public and searchable. A strict code of ethics must be implemented to mitigate against insider pacts (I’m looking at you, developers), double dealing, and conflicts of interest. This new organization must be squeaky clean, as any moral lapses could irrevocably endanger the entire project.

A Heartfelt Conclusion

My parents are refugees. They were forced from their country with nothing to restart their lives in an alien land. The Cuba they knew disappeared long ago. As their son, there’s a permanent psychological break, a chasm between my supposed madre patria and my sense of self. There’s nothing for me in Cuba, nothing with which to reconnect, even should I visit the island.

As a result, Miami, for its infinite faults and shortcomings, is my adopted, my only cultural, emotional, and spiritual motherland. It is the sole place on the planet where I feel comfortable, where I can unapologetically be myself.

I desperately don’t want to relive my parents’ trauma. I don’t want to be the next generation of refugees. I don’t want to abandon what my family built here. I want my children to inherit stability and a sense of being grounded on firm, dry land. So, my efforts to preserve my hometown from climate change are extremely personal. Miami isn’t a metaphor for humanity’s hubris or lack of foresight. It’s everything I have. And I’ll fight like hell to keep it. I hope the above essay convinces you this is not a hopeless struggle. More to the point, I hope you’ll join me.

If you like our stories, buy our book!